EU-Turkey relations: “Erdogan is not 12 feet tall”

- Date published: 19 June, 2023

Mr. Bechev, what does the re-election of Recep Tayyip Erdogan as president of Turkey means for EU-Turkey relations, if anything?

It will be more of the same essentially. This is certainly not a game-changer of any sort. The current relationship has been pretty bad for the past 7 or 8 years. However, it’s not abysmal. Despite all the frictions and problems, there is a certain resilience. You can see that in the continued importance of the EU as Turkey’s main trading partner, especially when it comes to Turkish exports, as well as an investment partner for Turkey. Moreover, support for Turkish EU membership remains relatively high, mainly because of the economic trouble that has beset Turkey. And on questions such as migration and combating climate change, Turkey will remain important for Europe.

So, it is certainly not a perfect relationship, to put it mildly, but I don’t see Erdogan’s re-election as leading to any sort of rupture, despite some people having a very sombre view of where things are headed.

What would have happened had the opposition candidate Kilicdaroglu won the election?

On the substantive side, some of the political prisoners would have been released, people like Osman Kavala. That would have been really important as these people have been stuck in jail on spurious charges for a long time. Also, a Kilicdaroglu victory would have given European decision-makers enough justification to open discussions on updating the Customs Union between Turkey and the EU. Ankara is keen on to include services as well as agriculture in the existing customs agreement. However, I don’t think Kilicdaroglu would have dramatically revised Turkish policy in the eastern Mediterranean. He might even have created risks vis-à-vis Cyprus and Greece.

"I don't think Kilicdaroglu would have dramatically revised Turkish policy in the eastern Mediterranean"

Dimitar Bechev, Oxford University Tweet

You mentioned EU enlargement. Is the debate about a possible EU accession of Turkey still alive?

Honestly, I don’t think it’s alive. It has not been alive for a long time, certainly after 2011, maybe for even longer. Having said that, neither the EU nor Turkey has an interest in formally terminating the negotiations. If anything, Erdogan wants the EU to pull the plug, in which case he would have a justification to claim ‘They don’t want us, it’s all their fault’. Likewise, certain EU members prefer that Erdogan terminate the negotiations. Others see some value in maintaining the facade of ongoing negotiations. But in practice, nothing is really happening and the action is elsewhere, on the Customs Union, the migration deal and a number of other fundamental policies.

Does the EU have any leverage over what is happening inside Turkey? Or has that gone?

It’s mostly gone. We don’t live in the golden era, i.e. the late 1990s and early 2000s. It’s very telling that during the election campaign, nobody referred to the EU as an anchor. Also, EU governments didn’t want to take a stand because it would have been seen as interference and as counterproductive. Nevertheless, the EU is a magnet. Even without exercising political leverage, you can play with conditionality, with the fact that there are conditions attached to visa liberalisation, there are conditions attached to the updating of the Customs Union. There’s also conditionality attached to climate change and the carbon border adjustment mechanism, which is about to kick in 2026. It will put pressure on Turkish institutions to adapt and implement policies in line with the EU’s preferences. So, we shouldn’t just write off the EU’s power when it comes to putting forward demands and conditions.

Tune in to the audio version of this interview, part of our new “EU Matters” podcast, available on Spotify.

In recent years, Erdogan seems to look more towards the South, towards the Muslim world. Are the days over when he was looking towards Europe, or could he turn around again?

Ideologically, people like Erdogan feel proximity to the Middle East. They are beholden to this idea that the world has moved beyond the West and that in the multipolar world, Turkey is one of the poles. In actual fact, he doesn’t need to be either with Western Europe and the United States or Russia or China. He can be on his own and play with everyone, including in the Middle East.

At the same time, are some hard realities. Economically, Turkey is anchored in the West. Although on the import side, China and Russia have a greater share than the EU, the EU is the market to which Turkey can export. Plus, you have the Customs Union with the EU and also NATO membership, which is the ultimate insurance policy for Turkey, facing Russia on the other side. So, even if you want to be a regional power and want to exert influence in the Middle East, sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, Europe and the Western connection remain important.

"Ideologically, people like Erdogan feel proximity to the Middle East. They are beholden to this idea that the world has moved beyond the West and that in the multipolar world, Turkey is one of the poles"

Dimitar Bechev, Oxford University Tweet

You mentioned the 2015 migration deal between the EU and Turkey. Is that a model for other countries in the region? And has that deal helped Erdogan to cement his power in Turkey?

On the first question, it could be a model and there is some political momentum building in this direction. Giorgia Meloni, the Italian Prime Minister, went to Tunisia recently, and we see governments in North Africa trying to also get the same treatment as Turkey, i.e. money in exchange for commitments on curbing migration.

How much did Erdogan get out of it? Of course, the money is not insignificant, especially in a time of economic disruption. Turkey now also faces an additional bill related to the earthquake. Turkey has done a great job in housing close to four million refugees, primarily from Syria, Afghanistan and other places. It’s not for nothing. But I’m not sure this has stabilized the regime because of growing resentment. Ten years ago, at the beginning of the Arab Spring, everyone in Turkey received Syrians with open hands. Now, political parties are bidding with one another about who will send more refugees back to Syria. Plus, Erdogan looks very keen to restore relations with Damascus and to start sending people back, if that is feasible at all. The refugee issue has exacerbated tensions in Turkish society, especially at a time when the economy is not doing very well.

Kilicdaroglu brought the issue up in his campaign, which for some came as a bit of a surprise given that he was seen as the liberal candidate. Was it a surprise to you? And did it work?

No, it was not a surprise in the least because it’s in the nature of coalitions challenging strongmen that they have to unite everyone across the spectrum, i.e. Liberals, nationalists, Islamists, conservatives, Kurdish nationalists, etc. That’s difficult because you cannot design policies to please everyone. The moment you embrace ethnic diversity, you face defections from the nationalists. So, it was not very easy for Kilicdaroglu to pull it off. Ultimately, it looked as if Erdogan landed in the soft spots. He could get some of the nationalist votes and promised to send some Syrians back home. But as he’s a very clever tactician, he also tried to say some nice words of solidarity and commitment to the Syrians. But Kilicdaroglu was torn apart for it. His party is historically not a force of liberalism, it’s very much the party of the secular regime before Erdogan. It has a nationalist backbone as well, it’s a coalition. There is a more liberal side but there are also really hardcore nationalists who are resentful of Syrians.

After 20 years of Erdogan: Has Turkey’s democracy disappeared, or will it disappear?

The Turkish democracy has shown resilience. You cannot just erase 70 years of competitive elections – despite all the flaws that Turkey always had. People are accustomed to the fact that their vote counts, they take part in political parties, membership there is quite high, and the political parties are real. It’s not a fake operation like you have in Russia and other parts of Eurasia.

"After many years under Erdogan, the playing field is unequal and his regime is quite entrenched. The elections were never fair, because of the access to media, access to state resources."

Dimitar Bechev, Oxford University Tweet

But after many years under Erdogan, the playing field is unequal and his regime is quite entrenched. The elections were never fair, because of the access to media, access to state resources.

Erdogan will push really hard to regain Istanbul, Ankara and the big cities he lost in the local elections in 2019. If it is done in a relatively transparent way, without rigging the vote, that will be a more positive scenario. If power is transferred in illegitimate ways, that will be really bad for whatever remains of the democratic system.

In the long run, I’m optimistic that Turkey will eventually, once Erdogan is not there anymore, reverse this kind of unconsolidated democratic system we have had – no rule of law, no transparency, a capturing of the state, back to a system where elections that are free and relatively fair.

Was the latest election free and fair, at least in comparison to previous elections?

We don’t know how free it was because we don’t have the full data yet. For instance, in many rural and small-town polling stations, you didn’t have opposition observers. It speaks not only volumes about the government; it also speaks volumes about the opposition’s incompetence in building up the operation. But it’s not easy to fight such a regime where the odds are stacked against you in so many respects.

Were you surprised about the election outcome?

I was surprised because all the polls suggested that the difference would be much narrower. I had suspected that there might be some hidden Erdogan votes, but he won by a very healthy margin. And my suspicion is that he didn’t win by rigging the election. He just played all the hands he has. Because again, the system is set up to favour the incumbent, as it is in all of those hybrid regimes.

So yeah, it’s depressing, but that’s how things are. And again, many European governments probably took the result as a mixed blessing. On the one hand, of course, Turkey is not going to rebuild its democracy. But on the other hand, they, the Europeans, have grown accustomed to Erdogan. He’s been there for a long time. He’s not an easy partner, but one can talk to and strike deals with him.

Secondly, compared to the previous election campaign in 2018 and compared to the referendum in 2017, there was no acrimony vis-à-vis key EU member states. Back in 2018, there was a crisis with Germany, a fight with the Netherlands. Ambassadors were recalled, and AKP ministers were able to campaign there. Now, Europe was absent in a positive and in a negative way. It was absent as the enemy against whom people could rally.

Is the Turkish diaspora under the control, or at least in part controlled, by Erdogan? He seems to have more supporters there than in Turkey itself…

Well, whatever I say should be taken with a pinch of salt as we need some more rigorous research by sociologists who have the data. But my impression is that the reason for that support is that historically, it was mainly people originating from Anatolia or eastern Turkey, i.e. conservative areas that tend to support Islamist politicians, who emigrated to countries like Germany. Secondly, Turkish nationalism is really a powerful force, and Erdogan symbolizes Turkey’s rise in world affairs, as an influential player respected around the world, and that resonates. Thirdly, those people in the diaspora are not economically tied to Turkey, their fortunes do not really depend on things like inflation or the strength of the lira. Hence voting Erdogan doesn’t carry these negative consequences, they are limited to people living in the country.

If you look at the challenges that the European Union has at the moment, with Russia, with climate change, with securing energy supplies, does Europe need Turkey and Erdogan more than Erdogan and Turkey need Europe?

I think it’s mutual dependence. In the short term, we, the EU, need Turkey. Energy is a good example. Azerbaijan has now become a gas supplier, and Turkey is a transit country. My own country, Bulgaria, which was cut off from Russian supplies, now gets a third of its gas from Azerbaijan.

The same dependence we see when it comes to controlling migration. However, it’s not that the EU hasn’t got any leverage. It does, and it has economic heft. So very often, commentators, especially in the media tend to portray Erdogan as 12 feet tall, that’s not the case. Even when he tried to play tough with the EU, as was the case in 2020 when he sent migrants over the border with Greece, that didn’t result in the EU caving in. On the contrary, Greece got help from Frontex to beef up its border.

The sad part, of course, is that the migrants were victimized by both sides, the Greeks and the Turks. Human rights were compromised in the process. But the EU is not weak, it has a lot of power, and it can also dictate conditions to Turkey. So, I see there’s a much more equal relationship where both sides have some strategic bargaining power. They have overlapping interests and conflicting interests.

The interview was conducted by Michael Thaidigsmann.

Dimitar Bechev is a lecturer at the School of Global and Area Studies at the University of Oxford and a visiting scholar at Carnegie Europe. Previously, he headed the Sofia office of the European Council on Foreign Relations. Bechev focuses on Central and Eastern Europe, the Balkans and Turkey as well as on Russian foreign policy, He has authored the books, “Turkey Under Erdogan: How a Country Turned from Democracy and the West”, and “Rival Power: Russia in Southeast Europe”.

Our most recent news

Former Estonian Foreign Minister: “We should make Russia understand that the West is not weak anymore”

In our most recent podcast edition of “EU Matters”, the Vice-Chair of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the European Parliament and former Estonian foreign minister, Urmas Paet, talks about the threat of Russia to Europe and the West’s support for Ukraine, as well as the recent developments in the Middle East between Israel and Iran.

Avital Grinberg appointed as General Manager of EU Watch

BRUSSELS – EU Watch announces the decision to appoint Avital Grinberg as the new General Manager, succeeding Michael Thaidigsmann at the helm of the organisation.

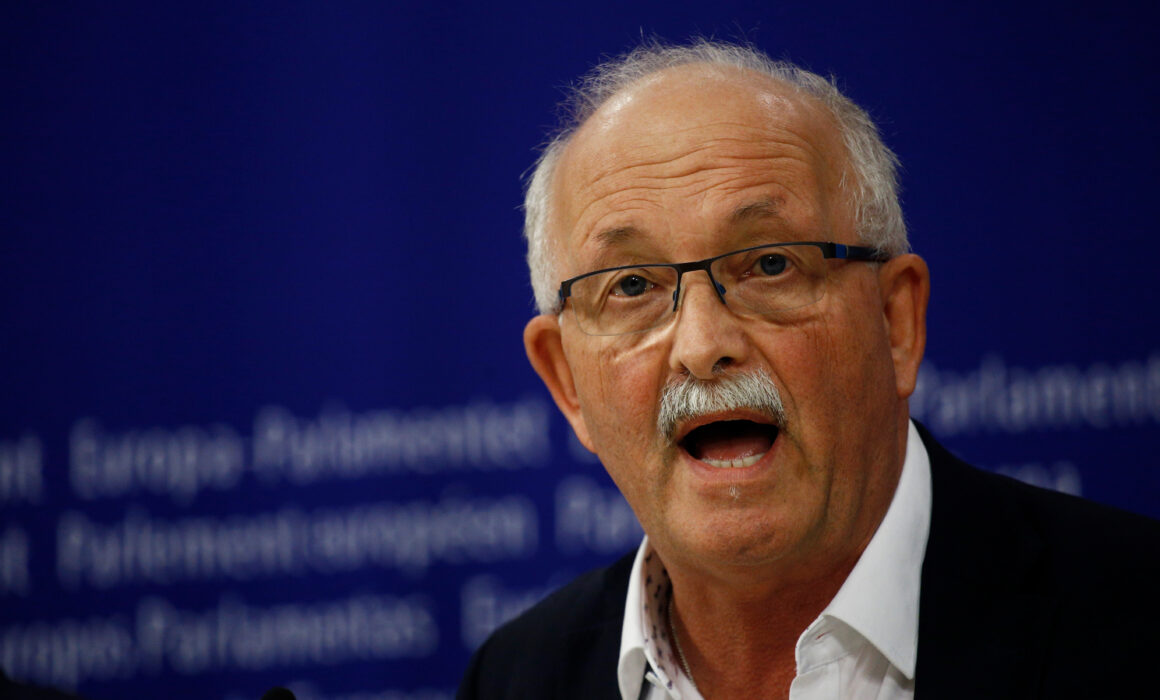

Veteran Socialist lawmaker: “We always knew that the EU would come under attack from guys like Putin”

German MEP Udo Bullmann talks about the importance of human rights in EU’s foreign policy, the EU as a player on the world stage and foreign interference in EU politics.

EU’s pivotal steps toward Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia: A personal perspective on the region’s historic shift

Professor Cristina Vanberghen delivers her opinion on the European Council’s decision to green-light negotiation talks with Ukraine and Moldova.

EU Sets Global Standard for AI Regulation

Professor Cristina Vanberghen delivers her analysis of the EU AI Act, which regulates the use of Artificial Intelligence in the Union.

Enhancing our understanding of the EU’s role in the Middle East

Professor Cristina Vanberghen delivers her analysis on the EU’s role in mediating Middle East conflicts.

Our newsletter

Let's keep in touch!

Subscribe to our newsletter

EU Watch - Website: DIREXION Web Agency

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.