The head of the Europe/EU research division at Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP), Nicolai von Ondarza, on how well the EU meets recent defence and security challenges.

Mr. von Ondarza, how do you assess the EU foreign policy since the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine? Has it improved with respect to speed of decision-making?

Many of the key decisions, such as adopting sanctions or using the European Peace Facility to deliver arms to Ukraine, were taken at what one could call lightning speed. The EU also managed to decide pretty quickly on additional elements, such as the enforcement of sanctions or penalties for violations. Even though Hungary delayed the sixth sanctions package against Russia for quite some while, in the end it only took around five or six weeks for it to be adopted. That is still much quicker than most other foreign policy decisions taken by the EU.

In other words, there has been improvement…

Yes. But there is still a lot to do to realize the EU’s full potential, not just with respect to the war against Ukraine, or more precisely, to putting the EU’s economic and foreign and security weight behind Ukraine. It was nonetheless noteworthy to see that all EU member states acknowledged the gravity of the situation and the responsibility of the EU to act collectively and decisively. This is despite the fact that divisions persist. So, some important procedures are still slower compared to the US or UK, but the EU has used its existing procedures to the maximum extent. It has improved in terms of the speed of its decision-making.

The European Union has no military capabilities of its own, and sanctions are often seen as having little effect. Is the foreign policy toolbox not half-empty?

In many conflicts and crises, the EU is first reaching to the sanctions policy, and perhaps the EU has overused the sanctions regime, but that is because of the economic might the EU has. Having said that, for me, there are two major shortcomings in the Common Foreign and Security Policy: the EU diplomacy and in particular the role of the High Representative for Foreign Affairs. Josep Borrell certainly has not been able so far to fill the gap which was to be filled with that position. Also, there is a lot of reluctance on the part of EU member states to task the High Representative with representing the 27 vis-à-vis third countries and to give him the necessary backing. Borrell’s catastrophic visit to Moscow in 2021 didn’t exactly help him.

So, the EU does not speak with one voice. Instead, we have seen Olaf Scholz, Emmanuel Macron and others phone Putin. There were very few coordinated diplomatic engagements by the 27 vis-à-vis the Russian leader. When it comes to trade, that is very different – here, the EU often negotiates with key international players like the US or the G7, but in the diplomatic field, it is absent or plays the second fiddle.

And in the military field – the Ukraine war has shown that very clearly – most EU member states still give NATO priority. Moreover, the American security guarantees are essential for Europe. Without the significant US military support for Ukraine – over 50 percent of what Kyiv received – the country could not have withstood the Russian invasion this well. NATO will remain the cornerstone of our collective defence in Europe. At the same time, the imbalance of the transatlantic relationship cannot continue. The EU needs more coordination and more capabilities in the military field, albeit not necessarily as EU-only ones.

Germany has been reluctant to provide military equipment to Ukraine, but nonetheless recently announced it will deliver armoured vehicles. What does Germany always seem to appear “late” in these decisions?

My personal assessment is that Germany has reluctantly moved forward in the type of support it provides to Ukraine. The main argument of the government is this: We don’t want to act alone, but in coordination with our allies, and we don’t want to escalate the war, we don’t want Germany to become a war party in a NATO-Russia war scenario. These arguments have been made again and again by the government. It is similar to what I explained above.

It appears that Germany is being pushed into every one of these steps and this has contributed to a worsening view on Germany amongst key allies, especially in Norhtern, Central and Eastern Europe. If you know that eventually, you will have to change your position, why don’t you do it straight away? I would be very surprised if we speak again in the summer if Germany would by then not have changed its position on delivering the Leopard tanks as well. I understand that the reluctance is connected to logistical difficulties. But the UK is trying to move forward, the US is pushing behind the scenes, and ff Germany were to act more proactively ahead of the curve it would also regain some of the trust it has lost in the last year.

A few days ago, the EU and NATO signed a declaration to strengthen cooperation. It encourages the Europeans to develop their defence policy but make it complementary and interoperable to NATO’s. Is that the end of Macron’s ambitions to have “strategic autonomy” for the EU?

Even Macron is pushing Europeans to develop more military capabilities in both EU and NATO contexts. The Europeans should not fall into what I would call an “intellectual trap”, i.e. playing NATO and EU against each other. The Iraq war from 2003 onwards showed that whenever EU countries are pushed to choose between NATO and the EU, the EU becomes divided and less effective.

If we strive for strategic autonomy, it should be done in my perspective, in a Euro-Atlantic context where military capabilities can be used by both EU and NATO. The EU can play a role here, it can coordinate, build up military capabilities, work on joint procurement, and enhance its defence industry. It should, however, not strive to develop EU-only capabilities that cannot be used for collective defence purposes or for United Nations operations. Competition between the EU and NATO should be avoided by those that seek strategic autonomy because if they don’t, they will likely lose the support of a majority of Central and Eastern European countries.

Given that the European Parliament does not have a real say in the foreign policy of the EU, would handing over more power to the Council not risk foreign policy losing its democratic legitimacy?

We should be mindful that foreign policy has always been a special area on the national level. In many EU states, it is largely the domain of the executive, while national parliament play more of a control function by scrutinizing the actions of the government rather than taking the decisions. Therefore, if we talk about the role of the European Parliament in foreign and security policy, there should be more control and scrutiny vis-à-vis the High Representative, the European Council and the Commission.

There are areas where if the EU’s role should be upgraded, when it comes to special monetary instruments. Parliament should have a bigger role in controlling these budgets. But as long as the EU doesn’t have its own military capabilities, parliamentary control should be primarily done by the national parliaments. The European Parliament can have a control function but should not take the ultimate decision on EU military operations.

This is the first part of the interview; the second, focusing on qualified majority voting, will be published in the coming days. The interview with the SWP expert was conducted by Michael Thaidigsmann and Nenad Jurdana.

Dr. Nicolai von Ondarza is a political scientist and researcher. He has been part of SWP for more than a decade.

Since 2020, he has acted as head of the EU/Europe Research Division.

His focus areas include the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) of the European Union as well as EU institutions and integration.

Our most recent news

Former Estonian Foreign Minister: “We should make Russia understand that the West is not weak anymore”

In our most recent podcast edition of “EU Matters”, the Vice-Chair of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the European Parliament and former Estonian foreign minister, Urmas Paet, talks about the threat of Russia to Europe and the West’s support for Ukraine, as well as the recent developments in the Middle East between Israel and Iran.

Avital Grinberg appointed as General Manager of EU Watch

BRUSSELS – EU Watch announces the decision to appoint Avital Grinberg as the new General Manager, succeeding Michael Thaidigsmann at the helm of the organisation.

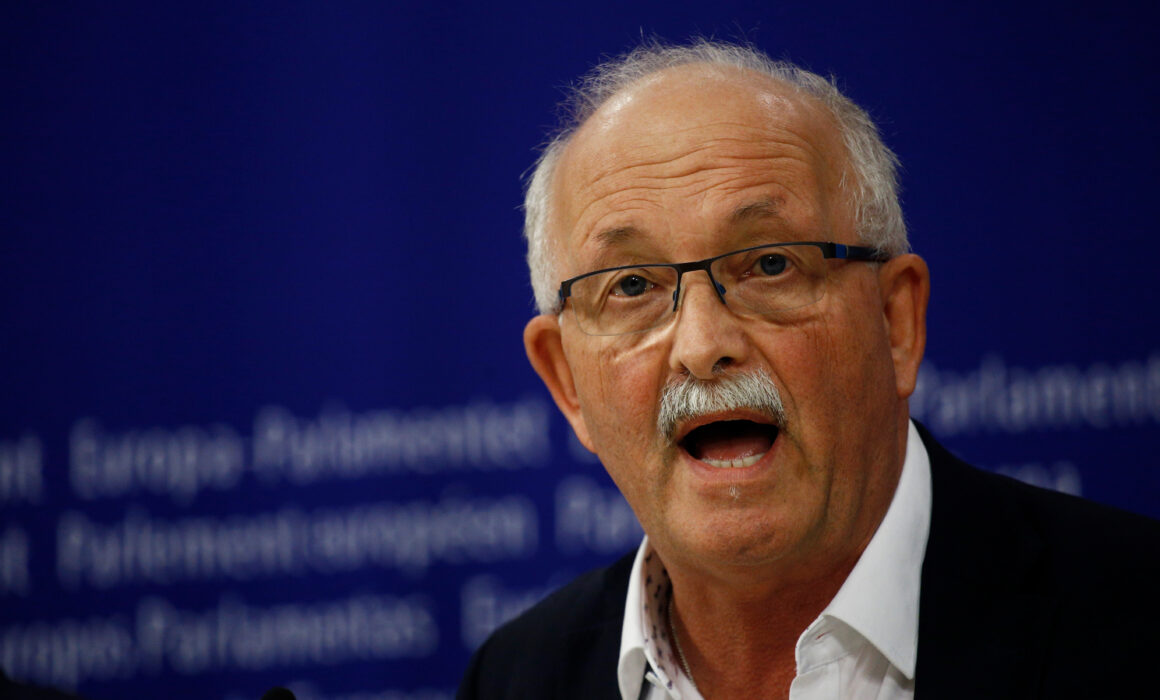

Veteran Socialist lawmaker: “We always knew that the EU would come under attack from guys like Putin”

German MEP Udo Bullmann talks about the importance of human rights in EU’s foreign policy, the EU as a player on the world stage and foreign interference in EU politics.

EU’s pivotal steps toward Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia: A personal perspective on the region’s historic shift

Professor Cristina Vanberghen delivers her opinion on the European Council’s decision to green-light negotiation talks with Ukraine and Moldova.

EU Sets Global Standard for AI Regulation

Professor Cristina Vanberghen delivers her analysis of the EU AI Act, which regulates the use of Artificial Intelligence in the Union.

Enhancing our understanding of the EU’s role in the Middle East

Professor Cristina Vanberghen delivers her analysis on the EU’s role in mediating Middle East conflicts.